The friar hurries down the hall. The grey morning has only darkened since dawn. Sleet pelts against the windows of San Domenico Maggiore.

He stops and raps at the door of a cell. There is a murmur from within, and he enters.

The friar sits down at a table covered with sheets of vellum. He rubs his hands together, blows into them, and looks up expectantly.

Father Thomas Aquinas broods in the light of two flickering candles. He’s looking in the friar’s direction, but past him, at some unseen object.

The friar, Reginald of Piperno, isn’t surprised. He was once Thomas’s student. For the past year, he’s been a fellow teacher here, at the monastery in Naples. He’s also Thomas’s secretary, the man to whom the great writer dictates his work. And for most of the past decade, he’s been Thomas’s confessor. So if anyone is used to these distracted silences, it’s Reginald.

It’s Dec. 6, 1273—the feast of Saint Nicholas. Thomas said this morning’s Mass, then returned to his cell. Reginald followed shortly thereafter, as is their custom. They’re working on what will become the Summa Theologica, a book intended for theology students. They’re midway through a section on the seven sacraments.

Reginald picks up a quill from the table, and searches for the inkwell. Then Thomas finally speaks.

“I can write no more.”

Only a little surprised, Reginald nods. The past few years have been hard ones for Thomas. The recent controversies at the University of Paris would have taken a tremendous toll on any normal man. And Thomas is as far from a normal man as Reginald can imagine.

Over the past five years, Thomas has produced the equivalent of what, centuries later, would be two or three novels—each month. If he needs a day off—well, he’s earned it, hasn’t he?

“Tomorrow, then—” Reginald begins. Thomas cuts him off.

“I can write no more,” he repeats. “Ever.”

Now Reginald meets his steady gaze. Thomas is no longer drifting. He’s laser-focused.

“I adjure you by the living almighty God, and by the faith you have in our order, and by charity that you strictly promise me you will never reveal in my lifetime what I tell you,” he says. Reginald shakes his head dumbly.

“Everything that I have written seems like straw to me,” says Thomas, “compared to those things that I have seen and have been revealed to me.”

There is silence again between the two men. The sleet rattles more insistently outside, and the candles gutter in a draft.

In his lifetime, Thomas Aquinas has written some eight million words. But he’s going to let God have the last one.

***

That revelation, whatever it was, seems to have been the greatest of several mystical experiences that Saint Thomas Aquinas experienced in the last years of his life.

The Italian theologian, nicknamed the “Dumb Ox” because of his size and frequent silence, is thought by many to be the finest philosopher who ever lived. He came up with a system that “baptized” Aristotle by merging his empirical rigor with Catholic doctrine.

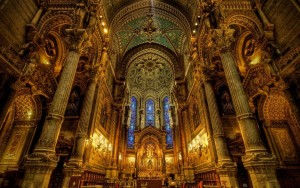

In the last year of his life, he completed a difficult essay on the Blessed Sacrament. When he finished, he threw down his thesis at the foot of the crucifix on the altar, and left it lying there; as if awaiting judgment. Then…the other Friars…declared afterwards that the figure of Christ had come down from the cross before their mortal eyes; and stood upon the scroll, saying, “Thomas, thou hast written well concerning the Sacrament of My Body.”

The astonished priests then watched Thomas rise several feet in the air.

And in Naples, late one night “in the stillness of the church of St. Dominic…a voice spoke from the carven Christ, and told the kneeling Friar that he had written rightly, and offered him the choice of a reward among all the things of the world.”

Aquinas’s response was, “I will have Thyself.”

In February of 1274, the pope himself had requested that Aquinas attend a general council of the church in Lyon, France. Undoubtedly, he would have preferred to stay in Italy, but he and Reginald dutifully set out for the journey. It did not last long.

While riding his donkey, Aquinas was struck in the head, perhaps by a falling branch. He stopped at his niece’s house, just north of Naples, but collapsed when he arrived.

He was taken to the nearby Cistercian monastery at Fossanuova, where he spent the next month. “This is my rest for ever and ever,” he said when he arrived. “Here will I dwell, for I have chosen it.”

Growing weaker, “he asked to have The Song of Solomon read through to him from beginning to end.” He also made a final confession that astounded his confessor. The priest “ran forth as if in fear, and whispered that his confession had been that of a child of five.”

Thomas Aquinas was just 49 years old when he died. G.K. Chesterton speculated that Aquinas was broken by the battles over his philosophy that occurred at the end of his life.

Aquinas’s detractors believed that Aristotle’s ideas could never be reconclied with Christian thought. His enemies had attempted to link him with the heresies of Siger de Brabant, a teacher at the University of Paris, and the leader of a radical group of arts masters and students.

“He never recovered from the shock,” Chesterton wrote. “He won his battle, because he was the best brain of his time, but he could not forget such an inversion of the whole idea and purpose of his life.”

But as biographer Denys Turner points out, Aquinas had always believed deeply in the power of keeping still. His final silence was, perhaps, a kind of statement.

Theology, Aquinas thought, emerges from silence. “And, all those words end in silence because, as he said, it is through the Son who is the Word that we enter into the silence of the Father, the Godhead itself, which is utterly beyond our comprehension.”

In the years that followed his death, it seemed as though Aquinas’s own words had achieved a philosophical victory.

The controversies of the 1270’s had divided the Dominicans, who mostly defended Aquinas, and the Franciscans, who mostly opposed him. But by 1323, less than 50 years after his death, Aquinas was canonized as a saint. And his views would later become “the preferred philosophy of the Roman Catholic Church.”

It seemed that the world had come to agree with something G.K. Chesterton would write centuries later: “The fact that Thomism is the philosophy of common sense is itself a matter of common sense.”

But the enemies of Aquinas had not disappeared. They would remerge, and this time—without Aquinas around to defend his views—they would do far more damage.

Those enemies are still very much with us today, and in fact seem more numerous than ever. They are the people who want to liberate the individual from every commitment, and who realize that the philosophies of Aquinas and Aristotle make them natural adversaries of this project.

A contemporary of Aquinas once said, “He could alone restore all philosophy, if it had been burnt by fire.”

The fire that was coming—the fire that has burned since the 14th century, which has burned out philosophy, as well as big chunks of our modern world—would attempt to do just that.

***

This has been an excerpt from Why We Think What We Think, a new history of Western philosophy from a Catholic perspective. The book, by Dan LeRoy, will be published by Sophia Institute Press in February 2024.

Author Bio – Dan LeRoy

Dan LeRoy is an author, journalist and teacher who has written for The New York Times, Rolling Stone, Newsweek, The Village Voice, Alternative Press, Esquire.com and National Review Online. Mr. LeRoy is certainly the only person in history to have contributed to publications founded by William F. Buckley, Jr. and by Gene Simmons of KISS. Meanwhile, his speculative fiction has appeared in several anthologies, and on the No Sleep podcast.

He has written several books, including a volume for Bloomsbury’s 33 1/3 series about the Beastie Boys classic Paul’s Boutique; Liberty’s Lions: The Catholic Revolutionaries Who Established America, and Dancing to the Drum Machine: How Electronic Percussion Conquered the World.

Since 2006, Mr. LeRoy has been the director of Writing and Publishing at Lincoln Park Performing Arts Charter School, near Pittsburgh, PA. He is also an adjunct professor of English at Franciscan University. For more information, visit his website, danleroy.com, or subscribe to his Substack newsletter, danleroysbonusbeats/substack.com

1 thought on “The Last Days of Saint Thomas Aquinas”

I would like to speculate considering that after the life changing (likely, final major) mystical experience he realised how limited his theology is and he wanted to grow from the error of assuming that becoming a child is growth in saintliness (their sinfulness made God deprived them of talents including scheming, hailed as innocence) while missing the basic point that using this life amidst sinners is the means God want babies to grow as men and women and free themselves of original sin enroute in which they are conceived. His re-listening of songs of Solomn and his admission of his confession had been that of 5 year old (my reading) he has finally found out that his hitherto conceived Kingdom of God is good only for children not of men and women into which human are created and saints are destined to live as God’s visible nature.